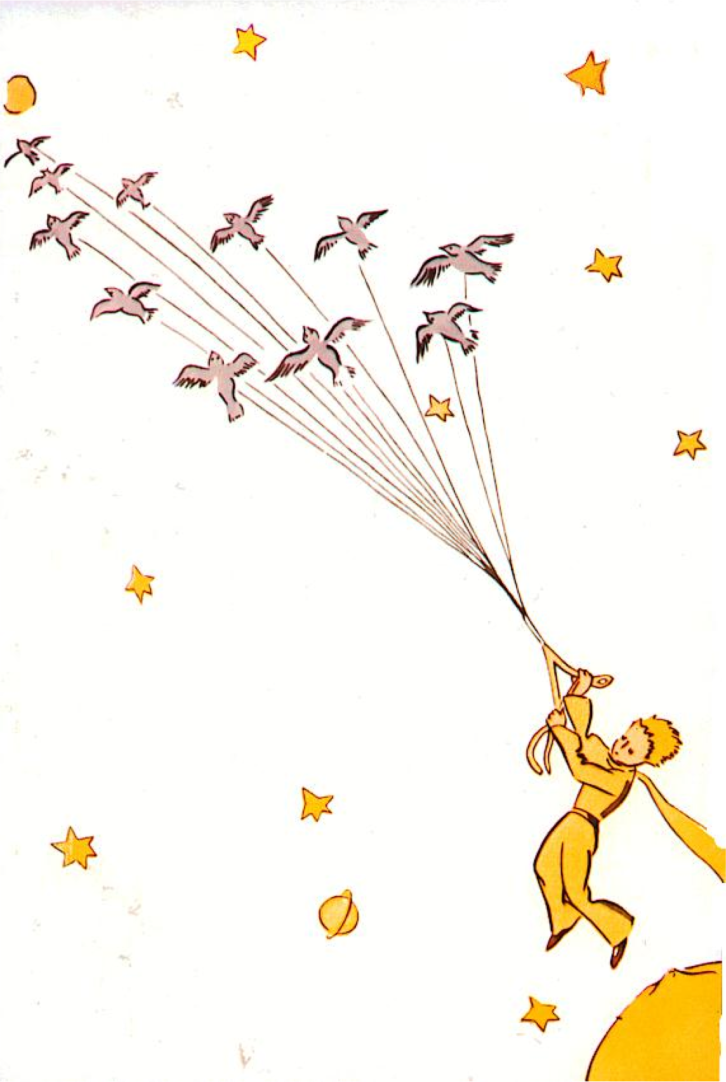

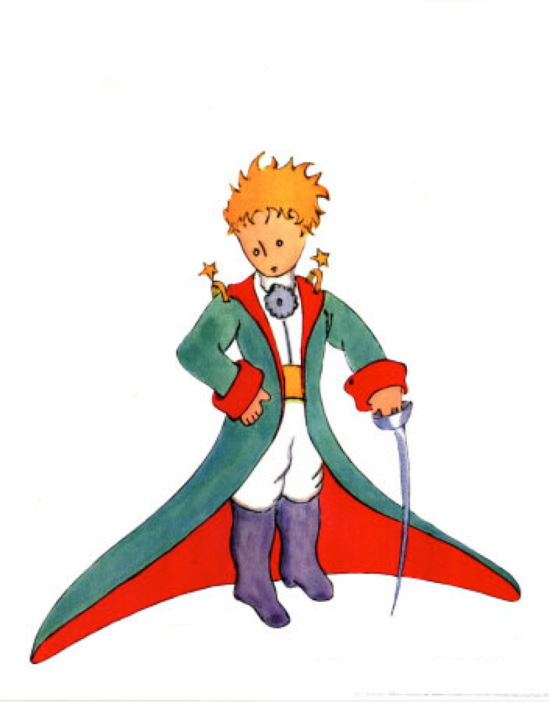

The Little Prince by saint-Exupérie

Summary by:

Vivian Manzardo

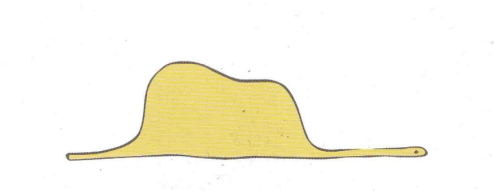

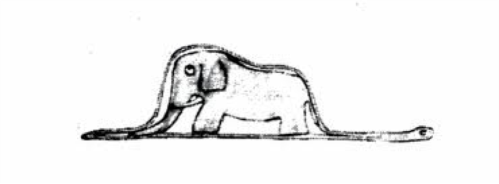

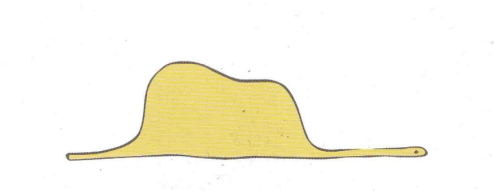

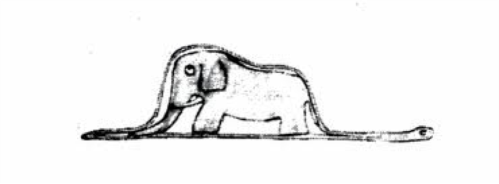

When I was six years old I succeeded in making my first drawing. My drawing Number One. It showed a boa constrictor digesting an elephant and it looked like this:

I asked the grown-ups if it frightened them. But they thought that it was only a hat and so I made another drawing. My drawing Number Two:

The grown-ups advised me to lay aside my drawings and dedicate myself instead to geography, history and grammar. So, at the age of six I gave up what might have been a magnificent career as a painter.

After many years, I learnt to pilot airplanes and I have to say that geography has been very useful for this.

Whenever I met a grown-up who seemed to me at all clear-sighted, I showed him my drawing Number One, which I have always kept. But he or she would always say:

“That is a hat.”

And so, after a while I gave up.

So I lived my life alone until I had an accident with my plane in the Desert of Sahara six years ago. Something was broken in my engine. I set myself to attempt the difficult repairs all by myself. It was a question of life or death for me: I had enough drinking water for a week.

At sunrise I was awakened by a little voice that said:

“If you please—draw me a sheep!”

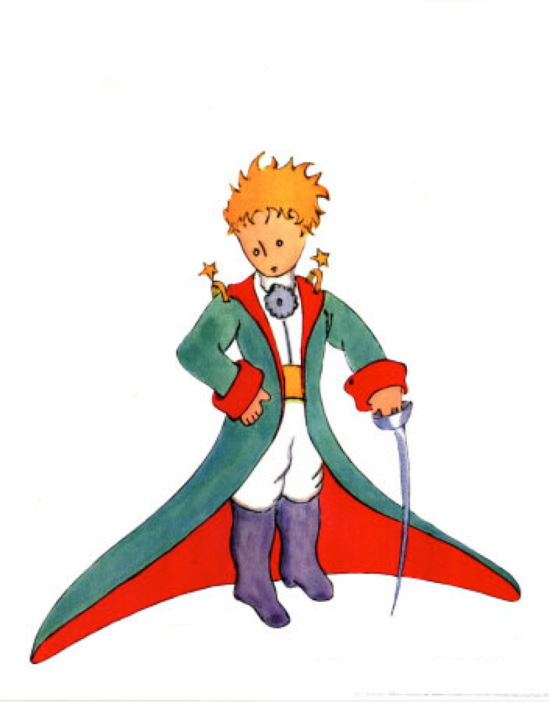

I jumped to my feet and saw a most extraordinary small person, who stood there examining me with great seriousness. I wondered what he was doing there, I was in the desert!

Then he said again:

“Draw me a sheep!”

But I had never drawn a sheep. So I showed him my picture Number One.

“No, no, no! I do not want an elephant inside a boa. I want a sheep. Draw me a sheep!”

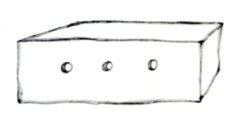

I made different drawings, but the first looked to him too sick, the second was not a sheep, but a ram, and the third was too old.

Finally I drew a box and told the little man that the sheep he wanted was inside the box. The little prince was finally satisfied.

It took me a long time to learn where he came from. The little prince never seemed to hear the questions I asked him.

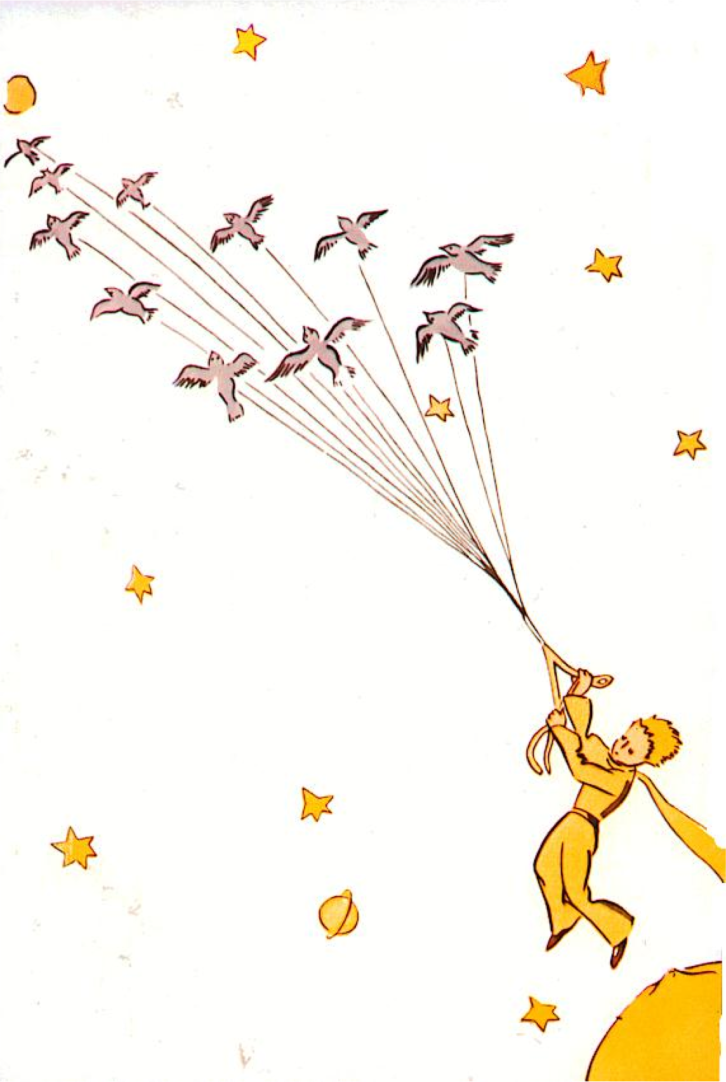

The first thing I discovered was that he came from another planet. The second fact I learned was that the planet where the little prince came from was scarcely any larger than a house. I have serious reasons to believe that the planet from which the little prince came from is the asteroid known as B-612, which has only once been seen by a Turkish astronomer in 1909.

“The proof that the little prince existed is that he was charming, that he laughed, and that he was looking for a sheep”

Each day I learned something new about the little prince’s planet, his departure from it, his journey.

On the third day, he told me that on his planet – as on all planets – there were good seeds from good plants, and bad seeds from bad plants — the seeds of the baobab.

So, he told me, when he had finished his own toilet in the morning, he had to take care of the “cleaning” of his planet. He had to pull up regularly the baobabs, as soon as he could recognize them.

On the fourth day, the little prince said to me:

“I am very fond of sunsets. Come, let us go and look at a sunset now.”

“But we must wait until it is time . . .” I said.

At first, he seemed very surprised and then he said to me, laughing:

“I am always thinking that I am at home!”

Sure, his planet was so small that he had only to move his chair a few steps to see the sun set another time.

A little later the little prince told me that one day he had seen the sun set forty-four times.

The next day the secret of the little prince’s life was revealed to me.

I discovered that, on his planet, the little prince had a flower that he loved. And he could not believe that even if she had thorns, she could been eaten by a sheep. He could not accept that. So I promised him that I would draw him a muzzle for his sheep.

His flower was different from all the others: she was unique. The flower was certainly not very modest, but — how beautiful she was!

Soon the flower revealed how complex she was: at night she wanted the little prince to put her under a glass globe, and during the day she wanted a screen to be protected from draughts.

On the morning of his departure the little prince put his planet in perfect order. He cleaned carefully his volcanoes — two active and one extinct. But he always cleaned also the volcano that was extinct because, as he said: “One never knows!”

The little prince also pulled up the last little shoots of baobabs. He believed that he would never return. In the end, he watered his rose.

“Goodbye,” he said.

“I have been silly,” said the flower. “I ask you to forgive me. Try to be happy . . . Please, do not linger like this. You have decided to go away. Now go!”

She did not want him to see her crying…

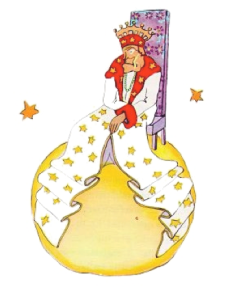

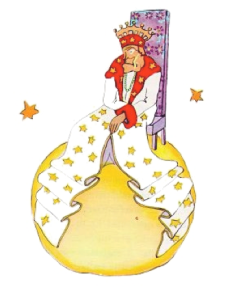

The first planet he visited was the asteroid 325.

It was inhabited by a king, who was an absolute monarch that did not tolerate disobedience.

But he was a very good man and made his orders reasonable. He required from each one the duty which each one could perform, not more.

The king tried to convince the little prince to stay on his planet and offered him to become minister of justice. But there were nobody to judge.

So, after a while, the little prince left.

“The grown-ups are very strange,” he said to himself, as he continued on his journey.

The second planet was inhabited by a conceited man. For him all the other men were admirers.

“Clap your hands, one against the other,” he directed the little prince when he saw him.

The little prince clapped his hands. The conceited man raised his hat in a salute.

“This is more entertaining than the visit to the king,” thought the little prince and began to clap his hands. The conceited man again raised his hat.

“Do me this kindness. Admire me,” said the man after a while.

“I admire you,” said the little prince. Then he went away.

“The grown-ups are certainly very odd,” he said to himself, as he continued on his journey.

The next planet was inhabited by a tippler. When

the little prince saw him, he asked him what he was

doing. The tippler answered that he was drinking in order

to forget that he was ashamed.

“Ashamed of what?” asked the little prince.

“Ashamed of drinking!” was the answer.

The little prince went away, puzzled. “The grown-ups are

certainly very, very odd.”

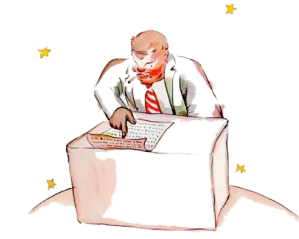

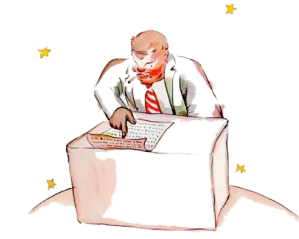

The fourth planet belonged to a businessman.

“Good morning,” the little prince said to him.

“3 and 2 make 5. 5 and 7 make 12. 12 and 3 make 15. Good morning. 15 and 7 make 22. 22 and 6 make 28. Phew! Than that makes 501’622’728.”

“Five hundred million what?” asked the little prince.

“501’622’728. I am concerned with matters of consequence: I am accurate.”

“Millions of what?” asked the little prince again.

“Millions of those little golden objects,” said the businessman, “which one sometimes sees in the sky.”

“Ah! You mean the stars? And what do you do with these stars?”

“Nothing. I own them.”

“And what good does it do to you to own the stars?”

“It does me the good of making me rich. And that makes it possible for me to buy more stars, if any are discovered.”

“And what do you do with them?”

“I administer them,” replied the businessman. “I count them and recount them.”

Then he continued counting his stars and the little prince went away.

“The grown-ups are certainly altogether extraordinary,” he thought simply.

The fifth planet was very strange. It was the smallest. There was just the place for a lamplighter and his lamp.

“Good morning,” said the little prince. “Why have you just put out your lamp?”

“Those are the orders,” replied the man. “Good morning.”

“What are the orders?”

“The orders are that I put out my lamp and then I light it again. Good evening.” And he lighted his lamp again. “I follow a terrible profession.”

“That man . . .” said the little prince to himself, as he left the planet, “. . . that man is the only one who does not seem to me ridiculous. Perhaps that is because he is thinking of something else beside himself.”

The sixth planet was ten times larger than the last one. It was inhabited by an old man.

“Oh look! Here is an explorer!” he exclaimed to himself when he saw the little prince coming.

“What are you doing?” asked the little prince.

“I am a geographer. I know the location of all the seas, rivers, mountains and towns.”

“Your planet is very beautiful… Has it any oceans, mountains, towns or rivers?”

“I could not tell you,” said the geographer, “because I do not have any explorers on my planet. The explorer goes out to count all those things and then he refers to the geographer. But he has to furnish proofs.”

The geographer was suddenly stirred to excitement.

“But you – you come from far away! You are an explorer! Describe me your planet!”

“I have three volcanoes. Two of them are active and the other is extinct,” said the little prince.

“I also have a flower.”

“We do not record flowers,” replied the geographer.

“Why that?”

“Because they are ephemeral.”

“Oh!” the little prince had his first moment of regret.

“What place would you advise me to visit now?” he asked the geographer.

“The planet Earth.”

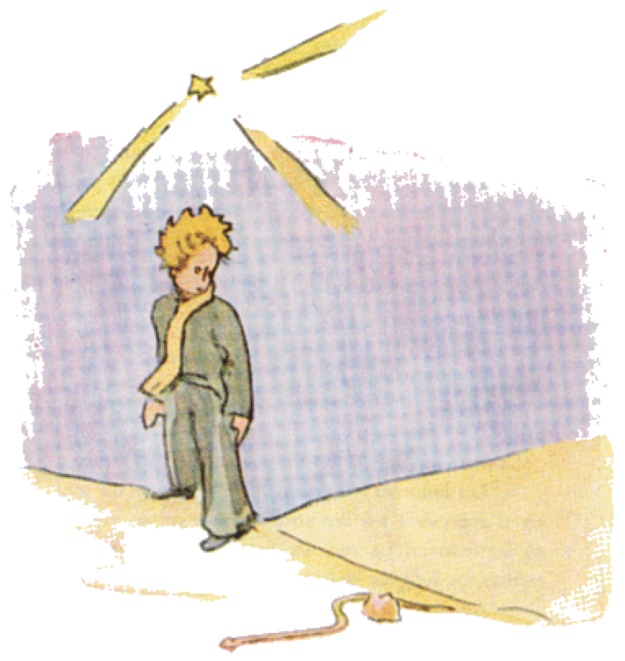

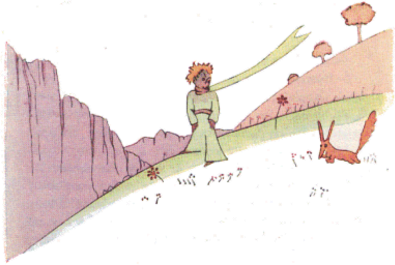

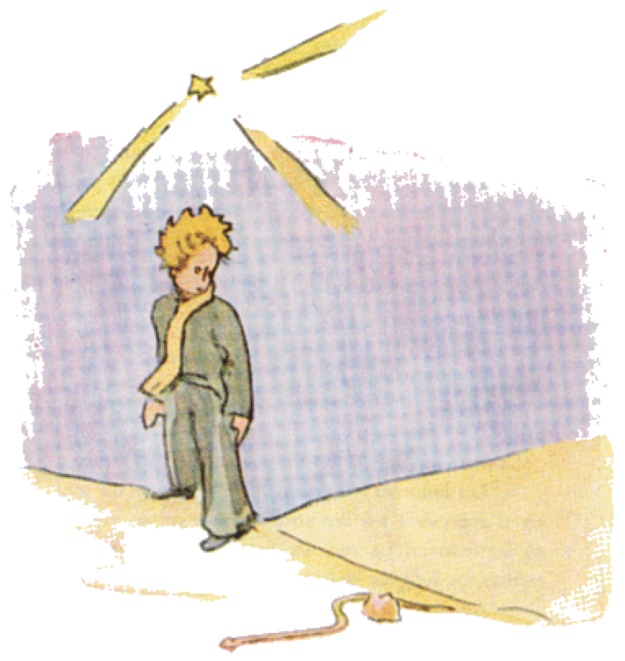

So, the seventh planet was the Earth. When he arrived on the Earth, the little prince was very surprised not to see any people. Then he saw something in the sand.

“Good evening,” he said.

“Good evening,” said the snake.

“You are a funny animal, you are no thicker than a finger . . .”

“But I am more powerful than the finger of a king,” said the snake. “I can carry you farther than any ship could take you. I can help you, some day, I can send you back to your planet.”

The little prince crossed the desert and climbed a high mountain. He did not find anyone. But then he came to a garden, all a-bloom with roses.

“Good morning,” he said.

“Good morning,” said the roses.

“Who are you?” he demanded, thunderstruck.

“We are roses,” the roses said.

“I thought that I was rich,” he said to himself, “with a flower that was unique in all the world; and all I had was just a common rose. That does not make me a great prince . . .”

And he lay down in the grass and cried.

“But you are innocent and true, and you come from a star . . .”

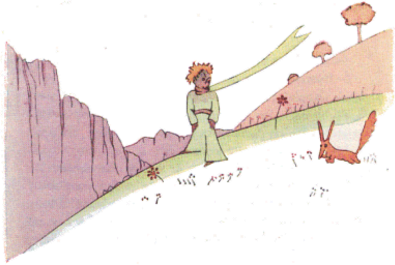

It was then that the fox appeared.

“Good morning,” said the fox.

“Good morning,” said the little prince, “Who are you?” he asked.

“I am a fox,“ the fox said.

“Come and play with me,” proposed the little prince.

“I am so unhappy.”

“I cannot play with you, I am not tamed,” replied the fox.

“What does it mean— ‘tame’?”

“Just that, to me you are still nothing more than a little boy who is just like all the others. And I do not need you. And you, on your part have no need of me. To you, I am nothing more than a fox like a hundred thousand other foxes. But if you tame me, then we shall need each other. To me, you will be unique in all the world. To you, I shall be unique in all the world . . . “

“There is a flower . . . I think she has tamed me . . .”

“It is possible,” said the fox. He gazed at the little prince, for long time.

“Please—tame me!” he said.

“I want to, but I have friends to discover . . .”

“If you want a friend, tame me.”

“What must I do, to tame you?” asked the little prince.

“You must be very patient, every day you will come and sit a little closer to me. And you must come at the same hour each day so if, for example, you come at four o’clock, then at three o’clock I shall begin to be happy.”

So the little prince tamed the fox. And when the hour of his departure drew near—- “Ah,” said the fox, “I shall cry.”

“It is your own fault,” said the little prince. “You wanted me to tame you . . .”

“Yes, that is so,” said the fox. “Go and look again at the roses. You will understand that yours is unique in the entire world. Then come back to say goodbye to me, and I will, as a present, tell you a secret.”

The little prince went away, to look again at the roses.

“You are not at all like my rose,” he said. “You are beautiful, but you are empty. Because it is she that I put under a glass globe; Because it is she that I have watered. Because she is my rose.”

And he went back to meet the fox.

“Goodbye,” he said.

“Goodbye,” said the fox. “Here is my secret, it is very simple: It is only with the heart that one can see rightly; what is essential is invisible to the eye.”

“What is essential is invisible to the eye,” repeated the little prince, so that he would be sure to remember.

“You are responsible for your rose . . .”

“I am responsible for my rose,” the little prince repeated, so that he would be sure to remember.

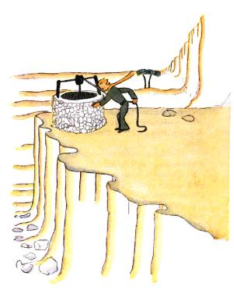

It was now the eighth day since I had had the accident with my plane and I was drinking the last drop of my water supply.

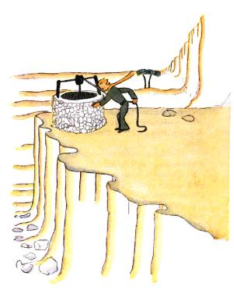

“I am thirsty, too,” said the little prince. “Let us look for a well . . .”

It is absurd to look for a well in the desert, but nevertheless we started walking. After some time the little prince sat down in the sand and said to me:

“What makes the desert beautiful, is that somewhere it hides a well . . .”

“Yes,” I said to him. “What gives it its beauty is something that is invisible!”

“I am glad,” He said, “that you agree with my fox.”

Then he dropped off to sleep. I took him in my arms and set out walking once more. And, as I walked so, I found the well, at daybreak. It was not like the wells of the Sahara. It was like a well in a village. Everything was ready for use: the pulley, the bucket, the rope…

I hoisted the bucket slowly to the edge of the well and set it there.

“I am thirsty for this water,” said the little prince. “Give me some of it to drink . . .”

I raised the bucket to his lips and he drank.

At sunrise the little prince said to me:

“You must keep your promise. You know—a muzzle for my sheep . . .

I am responsible for this flower . . .”

I took my rough drafts of drawings out of my pocket. The little prince looked them over and began to laugh.

“Your baobabs look like cabbages and it seems that the fox has horns,” he said. “But, children understand.”

So I drew the muzzle and gave it to him.

“I came down to Earth very near here. Tomorrow it will be one year,” he said.

“But now you must return to your engine. Come back tomorrow evening…”

I was a little frightened, but I left.

When I returned to the little prince that evening I saw him on top of the ruin of an old stone wall. He was speaking to someone but I could not see with whom.

“You have a good poison?” he was asking. “You are sure that it will not make me suffer too long?” I stopped my tracks, but still I could not see anything.

“Now go away,” said the little prince. “I want to get down from the wall.”

Then I saw it. There, before me, facing him, was one of those yellow snakes that take thirty seconds to bring to your life end. I took out my revolver and made noise to frighten the animal. I reached the wall just in time to catch my little man in my arms.

“Why are you talking with snakes?”

He looked at me very gravely.

“I am glad that you have found what was the matter with your engine,” he said. “Now you can go back home”

I was just coming to tell him that I solved the problem; how could he know that? He said:

“I, too, am going back home today . . .”

Then, sadly—-

“It is much farther . . . It is much more difficult . . .” his look was serious.

“At night you will look up at the stars. My star will be just one of the stars, for you. In one of the stars I shall be living. In one of them I shall be laughing. And so it will be as if all the stars were laughing.”

Then, quickly, he became serious:

“Tonight—you know . . . Do not come.”

“I shall not leave you,” I said.

That night he tried to leave without making noise but I woke up and followed him. He took me by the hand. But he was still worrying.

“it was wrong of you to come. You will suffer. I shall look as if I were dead. You understand . . . It is too far. I cannot carry this body with me.” Then he said:

“Here it is. Let me go on by myself.”

He took one step. I could not move. There was nothing there but a flash of yellow close to his ankle. He fell as gently as a tree falls. There was not even a sound.

And now six years have already gone by . . .

But I know that he did go back to his planet because I did not find his body at daybreak. And at night I love to listen to the stars. It is like five hundred million little bells . . .

Comment:

This is the fourth time I read this story, each time in a different language, and each time it teaches me somethig new and different.

The beaty of this story is in its simplicity. It teaches many things that people forget when they grow older. A child will read it like a fary tail, but this story is more then just that: it is also a story for grown-ups.

It helps people understand how feelings like love and friendship can make your life better.

Page after page, the little prince, with his innocent questions and answers, reminds us how importanti it is to be curious and to take care of the world and the people around us. To tame somebody means to show that one cares about him or her.

The author describes the world of the grown-ups with innocent children’s eyes and highlights the unreasonable and sometimes useless behavior of adults.

This is a strange and wonderful parable for all ages, with beautiful illustrations by the author.

(c) Vivian Manzardo